The UK maritime sector as a whole has been estimated to contribute between £14bn and £17bn of direct gross value added (GVA) annually to the UK economy. [1]Eddings, G., Chamberlain, A., Colaco, H. and Philips, I. (2020), ‘The Shipping Law Review: United Kingdom – England & Wales’, June., [2]Maritime UK (2019), ‘State of the maritime nation report 2019’, September.

The UK has a large industry supplying business services to the maritime sector, which contribute approximately £4bn to the UK economy.[3]CEBR (2017), ‘The economic contribution of the UK Maritime Business Services industry’, September.

Many of these businesses provide services to international clients, and thus most of their transactions can be considered to be internationally mobile transactions.

The UK has a market-leading 35% of global maritime insurance premia and 60% of protection and indemnity (P&I) clubs.[4]See: https://www.maritimeuk.org/about/our-sector/maritime-business-services/ (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Maritime legal services are also an area of strength, with London leading in dispute resolution services.

London is a major centre for mediation, with a total value of cases mediated each year of around £11.5bn, including many shipping cases.[5]Eddings, G., Chamberlain, A., Colaco, H. and Philips, I. (2020), ‘The Shipping Law Review: United Kingdom – England & Wales’, June. It is estimated that 80% of the world’s maritime arbitrations are dealt with in London.[6]LLMA (2018), ‘Call for Evidence Response Maritime 2050’. The UK is home to leading governance and regulatory bodies,[7]For example, the International Maritime Organization and the International Association of Classification Societies. and is home to the Baltic Exchange, a leading source of market information on trading and settlement of both physical and financial shipping derivatives.

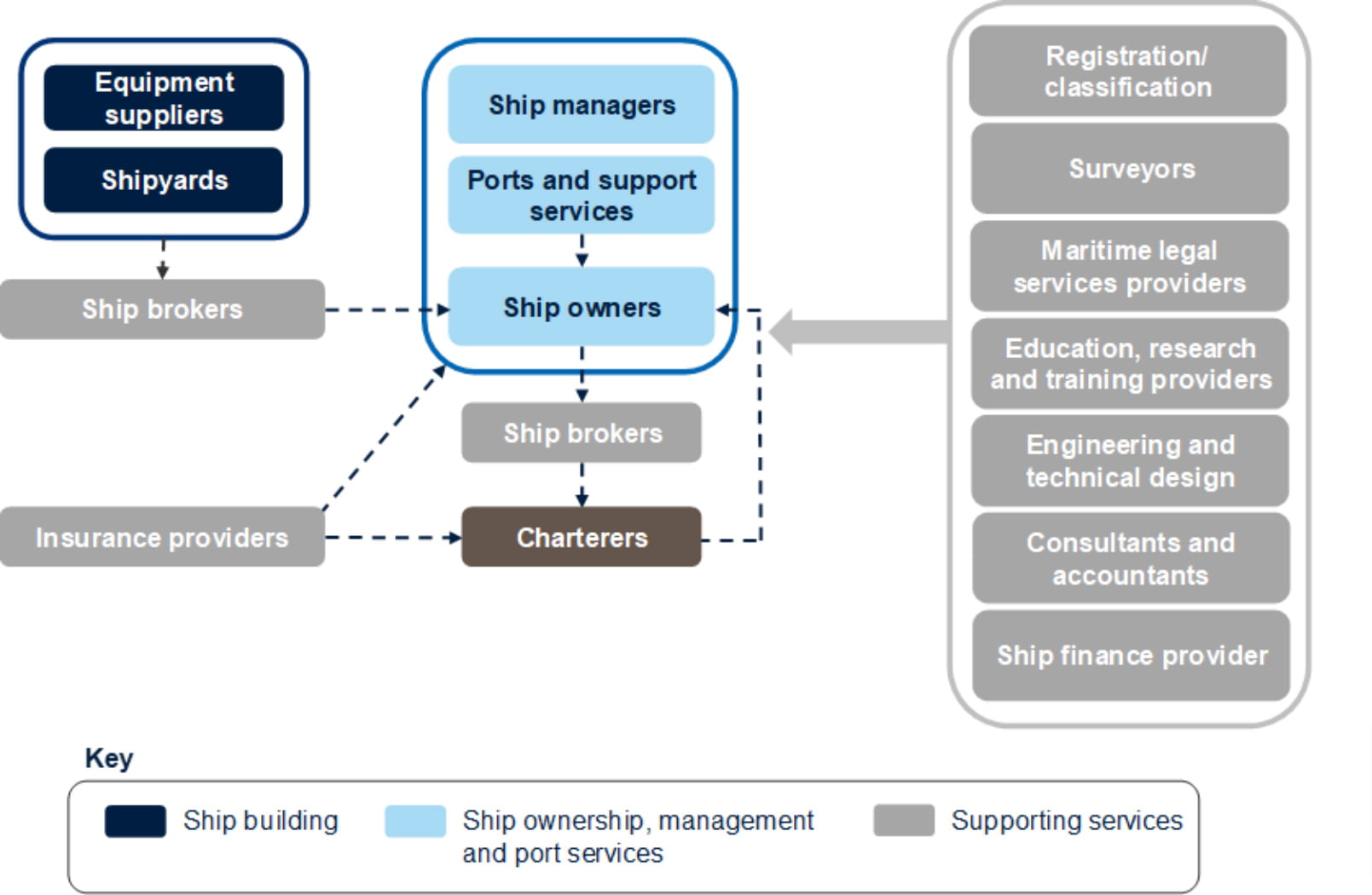

A stylised picture of this ecosystem is shown below in Figure A1.1. The diagram shows four broad categories of businesses involved in the maritime ecosystem:

- ship building—this comprises the shipyards where new vessels are built, as well as the suppliers of equipment and materials required;

- ship ownership, management and port services—this category includes ship owners (who may buy vessels via brokers) and ship managers who are commissioned to operate the ship. At ports, owners often rely on ship agents to liaise with various port authorities and port services;

- ship users—charterers hire a vessel from a shipowner. The charterer may own cargo itself, or use the vessel to deliver cargo on behalf of someone else;

- professional services—a wide variety of affiliate service providers are involved in the maritime sector. Ship brokers may act as intermediaries between ship builders, owners and charterers. Other important services include finance, engineering and insurance. Around 60% of the business services GVA in the maritime industry comes from insurance (see section A1.4 for a discussion of insurance).[8]PwC (2016), ‘The UK’s Global Maritime professional services: Contribution and trends’, research report published by the City of London Corporation. Classification societies establish and maintain technical standards, and surveyors examine vessels to report on their condition. The maritime legal sector provides advice to all participants in the ecosystem and assists in dispute resolution.